Get a free copy of Parental Rights & Education when you subscribe to our newsletter!

Evangelicalism has played a significant role in restructuring liberty in American to include slavery abolition. In this essay, Dr. Mark David Hall explains the challenges that Christians faced in pursuing abolition, namely combatting the cultural favor of slavery and even how Christians had to fight against other believers to secure abolition. Dr. Hall is the Herbert Hoover Distinguished Professor of Politics at George Fox University. He is the author, most recently, of Did America Have a Christian Founding? Separating Modern Myth from Historical Truth. Follow Mark on Twitter at @MDH_GFU.

Progressives today regularly criticize Christians, especially evangelical Christians, for being conservative opponents of racial progress. For instance, in a widely praised book, The Color of Compromise, Jemar Tisby writes that “when faced with the choice between racism and equality, the American church has tended to practice a complicit Christianity . . . and in so doing created and maintained a status quo of injustice.”[1]Similarly, Carolyn DuPont contends that “[n]ot only did white Christians fail to fight for black equality, they often labored mightily against it.”[2] It is certainly the case that some Christians have opposed racial justice, but many were leading advocates for freedom, justice, and equality in the United States.

In my previous essay for the Standing for Freedom Center, I acknowledged that America’s founders did not create a thoroughly just utopia. Grave evils remained and were perpetuated in the new nation — most notably slavery. Many founders were concerned with these evils and worked to ameliorate or end them. But whatever successes they had, these and other problems persisted into the 19th century. In this essay, I explore how Christians, often evangelical Christians, were on the forefront of battles to end slavery. My focus is on the antebellum era — that is, from the end of the War of 1812 until the start of the American Civil War.

The term “evangelical” has been used in a variety of ways, and there is no single accepted scholarly definition. Borrowing from the 19th-century minister Lyman Beecher, I consider evangelicals to be Protestants who adhere to historically orthodox Christian doctrines as articulated in the Apostles’ Creed and who emphasize the need for a conversion experience, salvation by grace through faith in Christ alone, and the authority of the Bible as interpreted by individuals.[3] Evangelicals are committed to sharing the gospel. Indeed, “evangelical” comes from the Greek word εὐαγγέλιον (euangelion), which means “good news.”

Evangelicalism in the United States is usually dated to the First Great Awakening, a series of revivals throughout America in the 1730s. Virtually every American of European descent thought of himself or herself as a Christian in the 18th century, but these revivals caused some self-identified Christians to doubt their salvation, have conversion experiences, and join an evangelical church or denomination. In the traditional telling of the tale, these revivals died down in the late 18th century and then blossomed again in the 1820s and 1830s in what is commonly referred to as the Second Great Awakening.

Scholars debate the extent to which these revivals waned in the 18th century and, if they did, when the Second Great Awakening began. But there is widespread consensus that the 1820s and 1830s were marked by numerous revivals that encouraged Americans to repent of their sins, have conversion experiences, and join evangelical denominations. The most striking growth occurred among Methodists, who went from being 2.5 percent of the population in 1776 to 34.2 percent in 1850.[4] It was also during this era that many Baptists shed their previous Calvinist views and became best characterized as evangelicals. By 1850, they constituted 20.5 percent of the American population.[5]Most Baptists and Methodists were evangelicals, but evangelicals could be found in other denominations as well. Scholars estimate that approximately 33 percent of adult Americans in antebellum America were accurately labeled “evangelical,” as opposed to 25 percent today.[6]

Today, we think of evangelicals as dominating the American south and being underrepresented in the north. In the early 19th century, the opposite was true. Evangelicalism was dominant in New England and was strong in the mid-Atlantic and western states. As well, evangelicals were well-represented in major metropolitan areas and among elites. It was not until the 1830s that evangelicalism swept the southern states and began to reshape the region into what is now sometimes called the Bible Belt.[7]

Many 19th century evangelicals believed that they could hasten Christ’s return if they spread the gospel and eliminated societal evils. Accordingly, they became energetic supporters of domestic and foreign missions. To help spread the gospel they founded, among other organizations, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (1810), the American Bible Society (1816), the American Sunday School Union (1824), the American Tract Society (1825), and the American Home Mission Society (1826).

These evangelicals also formed literally thousands of organizations aimed at alleviating suffering and reforming society. They were dedicated to benevolent activities such as feeding the poor, housing orphans, reforming prisons, fighting the abuse of liquor, aiding the mentally challenged, promoting peace, and educating the uneducated (including women and African Americans). Membership in these organizations often overlapped, and they were so prominent in antebellum America that they came to be referred to as the “Benevolent Empire.”

Women have always been central to the life of the Church and, in early America, they were sometimes able to influence politics indirectly through the advice they offered (Abigail Adams regularly shared her opinions with her husband) or publications (for instance, Mercy Otis Warren wrote under pseudonyms to support the patriot cause and, later, to oppose the adoption of the proposed Constitution). But they were almost always prohibited from voting and holding civic office. In antebellum America, women invented new ways to directly engage in political and social reform. They founded and led benevolent organizations; participated in political debates through essays, books, and public lectures; and lobbied legislators. Some of these women eventually joined what was then called the “woman movement” and advocated for social and political equality — especially the right to vote.[8] Because their contributions are often overlooked, I highlight the roles Christian women played in opposing the evils of slavery in this essay.[9]

As established in my first essay, virtually no founder defended slavery as a positive good and many were working actively to abolish it. Abolitionist societies flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and the leaders were committed to ending slavery and securing racial equality.[10] However, the invention of the cotton gin encouraged the expansion of slavery in the American South, and Southern leaders became increasingly defensive about the institution. After independence, most southern evangelicals opposed slavery, but by 1830 many had come to support it. Indeed, the two most prominent evangelical denominations split over the issue: Methodists in 1844 and Baptists in 1845.

Members of the Society of Friends, better known as Quakers, were among the earliest and most vocal opponents of slavery. In 1776, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting agreed to disown Quakers who held slaves in its jurisdiction (Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware). Friends remained among the most vocal critics of the institution in the 19th century. Among their greatest spokespersons were two sisters from South Carolina: Sarah and Angelina Grimké. The daughters of a prominent politician and slave owner from the state, Sarah moved to Philadelphia in 1821 and affiliated with the Quakers, and Angelina soon followed. Shortly thereafter, they became abolitionists.[11]

In 1835, Angelina joined the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (founded and presided over by another Quaker, Lucretia Mott). In 1837, the Grimké sisters embarked on an anti-slavery lecture tour where they spoke at “at least eighty-eight meetings in sixty-seven towns” to more than 40,000 people.[12] At the time, it was considered inappropriate for women to address mixed audiences, but the sisters did so anyway. They also published numerous essays to promote the abolition of slavery, including Angelina’s “1836 Appeal to the Christian Women of the South” (1836), Sarah’s “An Epistle to the Clergy of the Southern States” (1836), and Angelina’s “An Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States: Issued by an Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women” (1837).

Members of the Society of Friends were important leaders in the abolitionist movement, but if only Quakers were abolitionists the movement would never succeed. Even in Pennsylvania, they were a minority and they constituted only .003 percent of all Americans in 1855.[13] Fortunately for enslaved Americans, the far more numerous evangelicals soon became the hands and feet of the abolitionist movement.

Evangelical opposition to slavery can be traced back to the 18th century. English evangelicals, most notably William Wilberforce, led the fight to abolish the slave trade and slavery in the British Empire.[14] American evangelicals joined the battle as well. For instance, in 1790, the Baptist minister John Leland was able to convince the General Committee of Baptists to describe slavery as “a violent deprivation of the rights of nature, and inconsistent with a republican government” and to “recommend it to our brethren to make use of every legal measure, to extirpate the horrid evil from our land.”[15] Although Quakers founded most of the early American abolitionist societies, they recognized that they needed allies if they were to abolish slavery throughout the nation. They welcomed evangelicals to join them, often placing them and other non-Friends in positions of leadership within these societies so that abolitionism would not seem to be merely a Quaker idea.[16]

One of the most important evangelical opponents of slavery was the minister Charles Finney (1792-1879). He is best known as an evangelist who introduced new methods to revival meetings, such as holding protracted meetings that could last for days and the “anxious bench,” a row of seats in the front of revival meetings where those especially convicted of sin could sit until moved to repent. In 1835, he became a professor of theology at the recently formed Oberlin College, and he became its president in 1850. Oberlin was one of the first colleges to admit African Americans on the same basis as whites and, in 1834, women — thus making it the nation’s first coeducational college. Finney routinely denounced slavery, calling it a “great national sin,” and refused Communion to slaveholders. Under his leadership, Oberlin played an important role on the Underground Railroad.[17]

If Finney was one of the best-known male evangelists in the 19th century, Harriet Livermore (1788-1868) was among the best-known female evangelists. Raised a Congregationalist, she felt called to preach in 1821, and she regularly did so in Free Will Baptist churches in New Hampshire. As her fame spread, she was invited to preach throughout the nation. In the early 19th century, church services were regularly held in the U.S. Capitol, and in 1827 she preached there to an overflowing audience (President John Quincy Adams had to sit on a stair because all seats were taken). She returned to preach in the Capitol in 1832, 1838, and 1848.

Livermore abhorred slavery. In 1829-1830, when Virginia held a constitutional convention to create a new constitution, she sent a letter and petition to former President James Madison, who was attending the convention as a delegate, urging him to ban the institution. She explained that:

“I am a daughter of the happy part of our favored country called New England and of course an advocate for liberty. 2. I profess a belief in the gospel of Jesus Christ, & am consequently opposed to the Article of SLAVERY———3. I love my native country, therefore I am jealous of her laws, desiring they may be all equal, that no disproportion may offend the eye of Heaven, and draw divine judgments on a flourishing, enterprising, & (in some respects) happy Continent. 4. I feel myself in duty to my Savior, Master, & lawgiver, which is Christ Jesus, obligated to love my neighbor, [Matt. 22:39] especially to love the souls of men, women and children, for his Name sake, in whom there is all fulness of redemption, alike for Greek or Jew, barbarian Pythian bond or free, [Gal. 3:28] Glory, honor and praise for ever to his Great Name!”[18]

Like many evangelicals, Livermore drew direct lines between Christian liberty and the necessity of ending slavery. Alas, the letter and petition were not successful.

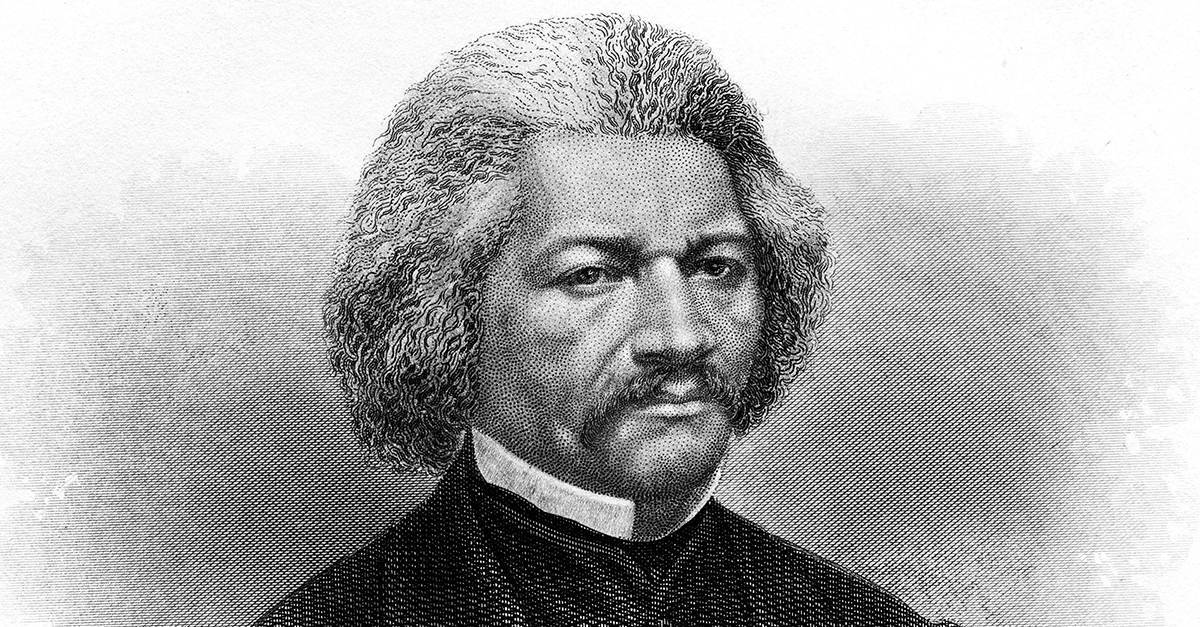

As might be expected, African Americans were committed abolitionists, the most famous of whom was Frederick Douglass (1818-1895). Born a slave in Maryland, he escaped to the north and became a leading abolitionist orator. He is best known for his autobiography Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845). In his books and speeches, he provided compelling arguments not only against slavery but against the all-too-common belief that African-Americans were inferior to whites.[19] He joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and in 1839 he became a licensed preacher.

Like Douglass, Isabella Baumfree (c. 1797-1883) was born into slavery. She escaped and later sued successfully for the freedom of her son. In 1843, she became a Methodist, and on Pentecost Sunday of that year she changed her name to Sojourner because she was convinced that God was calling her to “travel up an’ down the land, showin’ the people their sins, an’ bein’ a sign unto them.” She adopted “Truth” as a surname because she believed she was to “declare the truth to the people.”[20] She traveled widely to camp meetings, where she displayed a white banner imprinted with the words “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.” Once she attracted a crowd, she would “tells ‘em about Jesus, an’ I tells ‘em about the sins of this people.”[21] In 1851, she delivered one of the most famous abolitionist speeches of the era, a speech which later became known by the title “Ar’n’t I a Woman.”[22]

Early abolitionists often advocated ending slavery gradually, but in the early 1830s, some of them began to demand its immediate end. In 1831, William Lloyd Garrison started publishing his famous paper The Liberator, which aggressively advocated for the end of slavery. He and contributors to his paper had little patience with moderates, including Christian moderates. In the mid-1830s Garrison and other radical abolitionists began embracing highly unpopular views, including repudiating the United States Constitution, which Garrison called a “compact with the Devil.”[23] Garrison and his followers may have begun as orthodox Christians, but their radical views pushed them away from both America’s constitutional order and evangelicalism. Indeed, in 1858 the Garrisonian Wendell Phillips “denounced both George Washington and Jesus Christ as traitors to humanity, the one giving us the Constitution, the other, the New Testament.”[24] Very few Americans agreed.

Far more representative of evangelical reformers who opposed slavery were Arthur and Lewis Tappan, wealthy New York businessmen who funded a wide range of missionary and reformist organizations (including the aforementioned Oberlin College). They helped found the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833 and Arthur became its first president. The Tappans and their allies helped fund the printing and distribution of at least 1 million pieces of antislavery literature, and in 1837 the Society organized anti-slavery petitions that were delivered to Congress. Within a year, more than 400,000 men and women had signed these petitions. By 1838, the Society had 1,300 local branches and 250,000 members.[25]

In 1840, the abolition movement split into irreconcilable factions. Its leaders disagreed about whether to pursue gradual or immediate abolition, the role of women in the movement, and whether it was best to rely on moral suasion or political action. One faction formed a political party, the Liberty Party, which was committed to the principle of abolishing slavery immediately. Unfortunately for enslaved Americans, very few of its members won political office.[26] The admission of Texas as a slave state in 1845 led to the formation of the Free Soil Party in 1848. The main goal of this party was to keep slavery from expanding beyond the current slave states. It nominated former president Martin Van Buren to be president in 1848, and he garnered 10 percent of the popular vote. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 stoked tensions dramatically as it provided incentives for northern judges to declare African Americans brought before them by slave catchers to be slaves.

Inspired by the Fugitive Slave Act, Lyman Beecher’s daughter Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote one of the most influential novels in America’s history: Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). The book sold more than 300,000 copies in its first year and reached the hearts and minds of many Americans.[27] Stowe convinced numerous citizens that slavery, even in its more humane manifestations, was a grave evil. In response to accusations that she misrepresented the “peculiar institution,” in 1854 she published A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which documented the horrors of slavery. When Abraham Lincoln met Stowe in 1862, he reportedly observed that she was “the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.”

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 stipulated that the residents of each soon-to-be state would vote to permit or prohibit slavery. Advocates and opponents of slavery poured into the territories in hopes of influencing the outcome. A great deal of violence was committed by both sides, violence that included atrocities by the abolitionist John Brown (later famous for his 1859 raid on the federal arsenal in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia). Henry Ward Beecher (1813-1887), yet another of Lyman Beecher’s 12 children, played a role in this controversy. One of the most famous ministers of his day, he was a firm opponent of slavery. He raised funds to buy rifles for the abolitionist forces in Kansas, observing that the weapons would be more valuable than “a hundred Bibles.” Some of them were shipped in crates marked “books,” and the press soon referred to them as “Beecher’s Bibles.” Although contemporary Christians may learn lessons from our antebellum predecessors, shipping weapons into a bloody civil war zone is not one of them!

Also in 1854, the Republican Party was created by former members of the Whig and Free Soil parties. The new party formally opposed only the expansion of slavery, but many of its members were evangelical abolitionists. In 1860, the Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln was elected president without a single Southern electoral vote. Lincoln was no evangelical, but he was among the most theologically sophisticated of all presidents and he was committed to the principles of the Declaration of Independence.[28]

Historians, popular authors, and activists have spilled a great deal of ink debating what caused the Civil War, whether secession is constitutional, and Lincoln’s commitment (or lack thereof) to racial equality. Regardless of where one comes down on these debates, there is no doubt Lincoln’s issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, made ending slavery a central concern of the war. The 13th Amendment, which was ratified on December 6, 1865, banned slavery and did much to help realize the majestic promises of the Declaration of Independence.[29]

I began my last essay by observing that America’s founders believed it is possible for nations to sin and that God punished nations. Even the slave owner Thomas Jefferson worried that God would judge the United States for the sin of slavery. In his Second Inaugural Address, Lincoln interpreted the Civil War as a punishment sent by God:

“Fondly do we hope — fervently do we pray — that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether” [Psalm 19:9].”[30]

Lincoln was no evangelical, but he was correct in understanding slavery to be a national sin. The concluding lines of this address provide a thoughtful vision for how Americans should strive together to repair a nation torn asunder by war:

“With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan — to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”[31]

The “1619 Project” (discussed in my previous essay) errs grossly by viewing the whole of American history through the lenses of slavery and racism. It is far more accurate to see it through a Christian lens. From America’s earliest settlers to the present day, Christianity had far greater influence than racism. By the founding era, many civic and religious leaders had come to understand that slavery was an evil that must be ended. The cotton gin gave the peculiar institution a new lease on life and encouraged some southerners to portray it as a positive good. To their shame, some antebellum ministers even made biblical and theological arguments to support slavery.[32]

Fortunately, numerous Christians were committed to abolishing slavery in the United States. That slavery had to be ended through a bloody civil war is a tragedy, as Lincoln understood well. But the horrors of this war should not cause us to forget the men and women who were motivated by their Christian convictions to work tirelessly toward what they hoped would be its peaceful demise. We should not forget that it was ended peacefully in the American north and mid-Atlantic states, and Congress succeeded in prohibiting it from expanding into the upper mid-west. Many of these successes were due to the political activism of committed Christians. Today, many Christians are repulsed by politics.

[1] Jemar Tisby, The Color of Compromise: The Truth About the American Church’s Complicity in Racism (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2019), 17.

[2] Carolyn DuPont, Mississippi Praying: Southern White Evangelicals and the Civil Rights Movement (New York: New York University Press, 2013), 5.

[3] Lyman Beecher in The Autobiography of Lyman Beecher, ed. Barbara Cross (1864, reprint. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1961), 411-18. For further discussion, see Thomas Kidd, Who Is an Evangelical? The History of a Movement in Crisis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 4. Of course evangelicals were not, and are not now, a monolithic. Especially noticeable in antebellum America are differences related to race and geographic region.

[4] Mark A. Noll, A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1992), 153.

[5] Noll, A History of Christianity, 153; Richard Carwardine, Evangelicals and Politics in Antebellum America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 4-5.

[6] Curtis D. Johnson, Redeeming America: Evangelicals and the Road to Civil War (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1993), 4; https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/03/01/5-facts-about-u-s-evangelical-protestants/ (accessed October 5, 2019).

[7] Christine Leigh Heyrman, Southern Cross: The Beginnings of the Bible Belt (New York:

Knopf, 1997). Although many southerners were not evangelical, southern women participated in reform movements (albeit at lower rates than northerners). See Elizabeth R. Varon, We Mean to Be Counted: White Women and Politics in Antebellum Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

[8] Sandra F. VanBurkleo, “Belonging to the World”: Women’s Rights and American Constitutional Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 59-124; Julie Roy Jeffrey, The Great Silent Army of Abolitionism: Ordinary Women in the Antislavery Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

[9] Mark David Hall, “Beyond Self-Interest: The Political Theory and Practice of Evangelical Women in Antebellum America,” Journal of Church and State, 44 (Summer 2002): 477-99.

[10] Paul J. Polgar, Standard-Bearers of Equality: America’s First Abolitionist Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

[11] The Grimké sisters were the subject of Gerda Lerner’s landmark work, The Grimké Sisters from South Carolina: Rebels Against Slavery (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1967). A number of Quaker abolitionists drifted from Christian orthodoxy, including the Grimké sisters. See, for instance, Anna M. Speicher, The Religious World of Antislavery Women: Spirituality in the Lives of Five Abolitionist Lecturers (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2000), and Mark Perry, Lift Up Thy Voice: The Grimké Family’s Journey From Slaveholders to Civil Rights Leaders (New York: Penguin Books, 2001).

[12] Lerner, Grimké Sisters, 227.

[13] Timothy L. Smith, Revivalism and Social Reform in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Abingdon Press, 1957), 21.

[14] William Hague, William Wilberforce: The Life of the Great Anti-Slave Trade Campaigner (Orlando: Harcourt, 2008).

[15] Quoted in Thomas Kidd, God of Liberty, 157.

[16] Polgar, Standard-Bearers of Equality.

[17] Frances FitzGerald, The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2017), 40-43.

[18] Harriet Livermore to James Madison, Oct. 28, 1829, available at: https://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/default.xqy?keys=FOEA-print-02-02-02-1900 (accessed January 15, 2021).

[20] Sojourner Truth, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 164.

[21] Truth, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth, 164-65.

[22] For the original transcript of this speech and commentary on different editions of it, see Jeffrey C. Stewart’s introduction to The Narrative of Sojourner Truth (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), xxxiii-xxxv, 133-35.

[23] James Brewer Stewart, Holy Warriors: The Abolitionists and American Slavery (New York: Hill and Wang, 1997), 52.

[24] Smith, Revivalism and Social Reform, 180.

[25] Stewart, Holy Warriors, 70; Ronald G. Walters, American Reformers: 1815-1860. Rev. ed. (New York: Hill and Wang, 1997), 80-81; Jeffrey, Great Silent Army, 86-91.

[26] Perry, Lift Up Thy Voice, 177-87.

[27] Stewart, Holy Warriors, 165.

[28] Lucas E. Morel, Lincoln and the American Founding (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2020).

[29] Stewart, Holy Warriors, 191-95.

[30] Available at: https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=38&page=transcript (accessed January 13, 2021).

[31] Available at: https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=38&page=transcript (accessed January 13, 2021).

[32] Tisby, The Color of Compromise, 70-87.