Get a free copy of Parental Rights & Education when you subscribe to our newsletter!

The abortion debate is quite possibly hotter and more volatile than it has ever been. With the confirmation of a new conservative justice to the United States Supreme Court in 2020, the question of abortion rights has taken center stage once again in public discourse. This isn’t true only for pro-life advocates. The pro-choice community has expressed great concern for the overturn of Roe v. Wade and the inevitable impact it will have on abortion.

This has resurfaced the many layers of questions in the abortion debate:

These layers are numerous, making public discourse difficult and fraught with confusion.

Fundamental to these questions is the question of personhood with respect to the unborn. On this question of personhood and the rights of the unborn, nearly every pro-choice argument boils down to one of three views. They either (1) deny that the unborn are persons, (2) doubt whether we can know if the unborn are persons, or (3) defend women’s rights to abortion even if the unborn are persons. How should pro-life advocates address the challenges from pro-choice advocates? Do we have reason to believe that the unborn are persons of intrinsic value, that they are moral agents possessing rights and duties like every other human being?

This multi-part series titled “Personhood and Pro-Choice Arguments” will address the three pro-choice views on personhood and how pro-life advocates can respond to them.

Argument 1 — Denying the Unborn are Persons

The first view denies that the unborn are persons. It does not deny that the unborn are biologically human; it simply denies their status as persons. It distinguishes the product of conception (biologically human) and personhood (human being). Pro-choice advocates may acknowledge that born humans are persons with rights, but they may deny that the unborn are also persons. The unstated assumption in this view is the belief that born human beings are in some way fundamentally different than the unborn. To challenge this assumption, pro-life advocates should ask a key question:

Is there any essential difference between a born human being and an unborn human being? Of course, there are many differences between these two, but are these differences relevant for determining personhood? Do they render the unborn fundamentally different than the born such that the former is not a person while the latter is a person? A pro-life response would argue, no: the unborn and born are essentially the same despite any differences they have. A helpful pro-life argument called the SLED test can illustrate this point.

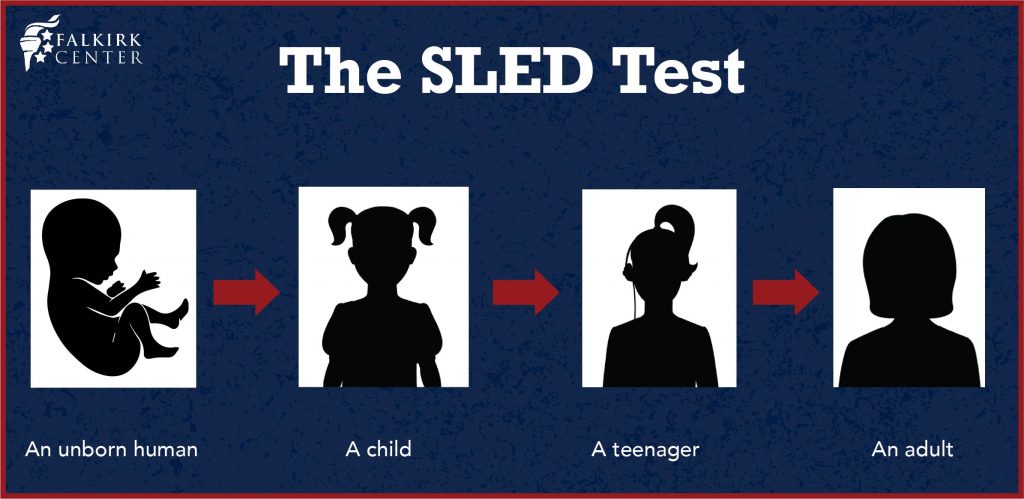

First proposed by ethicist Stephen Schwarz in The Moral Question of Abortion, the SLED test maintains that the only differences between the unborn and born human are size, level of development, environment, and degree of dependency. In other words, in the case of any individual the differences between their unborn-self and their born-self boil down to these four differences, and none of these differences are relevant to determining personhood. None of these differences grant personhood to one and not to the other.

As an example, the SLED test asks us to consider a fully grown woman and imagine her life at four stages—unborn, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. At each stage, there are differences in her size, level of development, environment, and degree of dependency, but none of these differences disqualify the unborn from personhood. If the adults, teenagers, and children are considered persons, then so should the unborn.

We recognize the people come in all shapes and sizes, but we do not ascribe the property of personhood based on size. A child is obviously smaller than a teenager or an adult. Does this imply that the child is not a person? Of course not. The unborn is also smaller than an adult, but if size does not disqualify a child from personhood, why should size disqualify the unborn from personhood?

Size is simply irrelevant to determining whether the unborn are persons.

We also recognize that some human beings are not as developed as others, whether mentally, emotionally, or physically. A young girl is not as developed as a teenager or an adult woman, but would it follow that the girl is not a person? Likewise, the unborn human is not as developed as an adult, but does it follow that the unborn is not a person? If level of development does not disqualify a child or a teenager from personhood, why would it disqualify the unborn? The unborn possess the same innate capacities for rationality, consciousness, language, and moral agency as children, teenagers, and adults do. These capacities are simply less developed within the unborn, just as they are less developed with younger humans who are born. Even a fetus shows emotion based on their level of rationale. They respond to pain and even express themselves by kicking.

The development of the unborn is not inert, but simply less.

Our environment changes frequently, but this does not seem to bear on whether or not we are persons. The unborn, the child, the teenager, and the adult are all in different environments, but if environment (e.g. location) has no bearing on whether the child and teenager are persons, why would it be relevant for determining the personhood of the unborn? How does the difference in location between an unborn infant and born infant somehow confer personhood on the one but not the other?

Where you are does not determine who you are.

Human beings are dependent on one another to various degrees, but as we can see, degree of dependency is also irrelevant to determining personhood. The small child is dependent on her parent to a much greater degree than a teenager would be. Does this warrant the conclusion that the child is either not a person or less of a person than the teenager or adult? Likewise, the unborn human is dependent on its parent to a great degree. If children and teenagers are considered persons, why not the unborn?

If dependency does not disqualify the child or the teenager from personhood, how could it disqualify the unborn from personhood?

As we can see, the only differences between an unborn human and a born human are not relevant for determining the status of personhood. If one were to deny personhood to the unborn on account of one of these differences, logically it seems that personhood could be denied to born human beings. If we confer personhood on born humans, we must confer personhood on unborn humans as well. Therefore, it is illogical to deny personhood to the unborn on these grounds. One’s size, level of development, environment, or degree of dependency does not determine one’s intrinsic value.

In response to this argument, pro-choice advocates may acknowledge that we cannot outright deny the personhood of the unborn, but they may object that the personhood of the unborn cannot be known with certainty and therefore society should give preference to abortion rights. In contrast to the denial argument, this objection is an argument from skepticism about the personhood of the unborn. It attempts to justify abortion on account of our supposed ignorance regarding the personhood of the unborn. In Part 2 of this series, we will critique the argument from skepticism and show that skepticism actually counts against abortion, not for it.

If you like this article and other content that helps you apply a biblical worldview to today’s politics and culture, consider making a donation here.