Get a free copy of Parental Rights & Education when you subscribe to our newsletter!

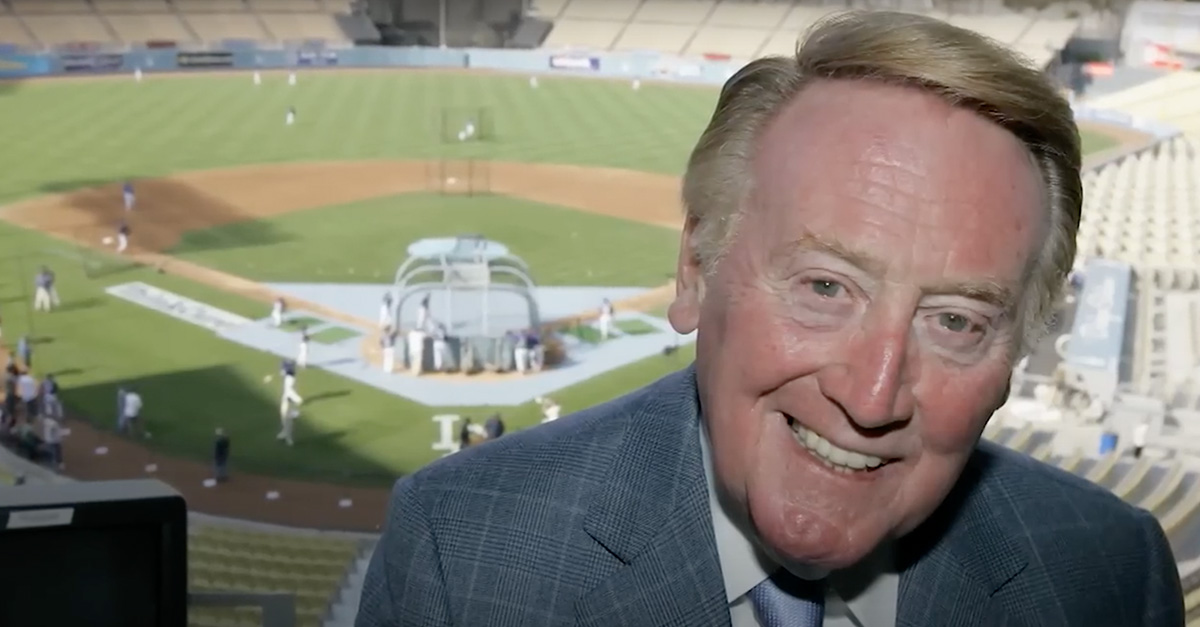

“God has been incredibly kind to allow me to be in the position to watch and to broadcast all these somewhat monumental events. I’m really filled with thanksgiving and the fact that I’ve been given such a chance to view. But none of those are my achievements; I just happened to be there.…”

–VIN SCULLY

“It’s time for Dodger baseball…Hi everybody and a very pleasant good evening to you, wherever you may be.”Completing this poll entitles you to receive communications from Liberty University free of charge. You may opt out at any time. You also agree to our Privacy Policy.

That was the opening Dodgers fans heard so many times over the course of Vin Scully’s 67-year career as broadcaster for the team. Sadly, though, it will only ever be heard again in recordings and in the memories of fans as the consummate communicator died Tuesday at the age of 94.

Scully’s death has solicited tributes from columnists, analysts, athletes, broadcasters, and friends from around the country, replete with examples of his greatest calls. There is a wealth to choose from out of a career that began in 1950. For some of the most memorable moments in the history of sports, Scully was there. There’s his call of the ball going through Bill Buckner’s legs in the 1986 World Series, Dwight Clark’s “The Catch” in the 1981 NFC Championship, Kirk Gibson’s hobbled home run in the 1988 World Series, and so many more.

These moments stand out on their own, but in part it was Scully’s announcing that made these events cultural timestamps.

Take Scully’s call of Sandy Koufax’s perfect game in September 1965. Koufax had thrown three no-hitters in his career but had never thrown a perfect game; it’s such a tough feat that only 23 pitchers in sum have done it since 1880. Scully painted a colorful, Da Vincian portrait of what the atmosphere felt like headed into the ninth inning with Koufax needing only three outs for history.

“The Dodgers defensively in this spine-tingling moment: Sandy Koufax and Jeff Torborg. The boys who will try and stop anything hit their way: Wes Parker, Dick Tracewski, Maury Wills and John Kennedy; the outfield of Lou Johnson, Willie Davis and Ron Fairly. And there’s twenty-nine thousand people in the ballpark and a million butterflies.”

A few moments later Scully remarked, “I would think that the mound at Dodger Stadium right now is the loneliest place in the world.”

When Koufax struck out the final batter, Scully celebrated, “Swung on and missed, a perfect game!”

Then he stayed silent for 38 seconds, letting the listener hear the sound of an ecstatic crowd during what was a once in a lifetime experience. Scully went on to lyricize, “And Sandy Koufax, whose name will always remind you of strikeouts, did it with a flourish. He struck out the last six consecutive batters. So, when he wrote his name in capital letters in the record books, that ‘K’ stands out even more than the O-U-F-A-X.”

Letting the moment breathe was a trademark of Scully’s. In Scully’s call of the injured Kirk Gibson’s game-winning home run in Game 1 of the 1988 World Series, he introduced the moment saying, “Look who’s coming up.” He added, “You talk about a roll of the dice, this is it.” When the ball left Gibson’s bat Scully said, “High fly ball into right field…she is gone!” Then nothing but the cheer of the crowd for over a minute. After the perfectly timed pause, Scully delivered his famous summary: “In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened!”

In an interview with Atlanta Braves broadcaster Chip Caray, son of the famous Skip Caray and grandson of the even more famous Harry Caray, Scully said that his habit of pausing began when he was 8 years old growing up in New York and listening to the radio when he was “intoxicated” with the roar of the crowd. “All throughout my career I like to call a play and then shut up because for a brief moment I’m 8 years old again, I’m listening to the crowd.”

While Dodgers fans named Scully’s call of Gibson’s homer their favorite in Scully’s final season with the team in 2016, it was a different home run that the wordsmith said was his most important.

Scully was on the mic when Hank Aaron hit home run number 715 to break Babe Ruth’s record in Atlanta in 1974. After delivering his call of the home run, Scully again fell silent before following up with, “What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world — a black man is getting a standing ovation in the deep South for breaking the record of an all-time baseball idol.”

Scully told Caray, “This was the greatest impact homerun sociologically. I mean, here is a black man in the deep South getting an absolute love ovation for breaking the record of a white icon. To me, that’s what made that home run the most important home run I ever called.”

The hall-of-fame broadcaster had begun his career in Brooklyn just a few years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier with the Dodgers, becoming the first black man to play in the Majors. He witnessed the racism Robinson faced and had then witnessed the Deep South embrace Aaron less than 30 years later.

Scully’s mastery of mental imagery went beyond historic calls to the everyday moments of the game. He famously humanized players of both teams and regaled listeners with personal anecdotes, as well as superior storytelling. The Wrap compiled some of Scully’s memorable calls, not only the ones I mentioned, but the more humorous ones, such as Scully translating a manager’s profanity-laced tirade for a G-rated audience, learning about Twitter, narrating a brawl between teams, and explaining the history of beards — all while keeping up with calling the game.

Some Dodger fans feel like they have lost a father figure, a man whose calm and reassuring voice let them know everything would be okay and whose gentlemanly behavior taught them how to act. One fan said, “It’s like your childhood…is now really over.”

Indeed, the passing of Scully feels like the end of an era that many Americans wish they could go back to. I think of two calls that remind me of the shift in culture we have experienced. The first was in 1976 as the Dodgers played the Chicago Cubs and two protestors ran onto the field. The protestors knelt down to burn an American flag before Dodger Rick Monday ran in and snatched up the flag. With shock in his voice, Scully said, “I think the guy was going to set fire to the American flag. Can you imagine that? Monday, when he realized what he was going to do, raced over and took the flag away from him. And Rick will get an ovation and properly so. And on the message board it just says, ‘Rick Monday, you just made a great play.’”

The other was a sidebar Scully did on socialism where he said, “Socialism, failing to work as it always does, this time in Venezuela. You talk about giving everybody something free, and all of the sudden there’s no food to eat. And who do you think is the richest person in Venezuela? The daughter of Hugo Chavez. Hello. Anyway, 0 and 2.”

In a day where members of sports media and athletes applaud protesting the flag and promoting wokeism which divides the country, Scully, who lived through the Great Depression, World War II, and the Cold War, remained loyal to his principles and his country and told it like it was.

What grounded Scully was his faith. A devout Roman Catholic, Scully told Angelus News that through all the hardships he faced, such as losing his father when Vin was 5, losing his first wife, Joan, and the tragic death of his son Michael, “Faith is the one thing that makes it work, makes me keep going. You appreciate what you’ve been given. You know, this isn’t the only stop on the train. There’s one big one we’re still waiting for. I used my faith to guide me straight and narrow and strong, for sure. I think about that every week when I’m in line going up to the rail to receive Communion. That’s a pretty important moment. It always was and always will be.”

While others have heaped praise on Scully for decades, he never took credit for his historic calls. “God has been incredibly kind to allow me to be in the position to watch and to broadcast all these somewhat monumental events. I’m really filled with thanksgiving and the fact that I’ve been given such a chance to view. But none of those are my achievements; I just happened to be there.… I know some people won’t understand it, but I think it has been God’s generosity to put me in these places and let me enjoy it.”

It was his humility and kindness possibly more so than his gift for language or his voice that made Scully beloved by all. Everywhere you look there are stories of his impact on players, broadcasters, and fans—all because of his grace and compassion. Stories of Scully taking time for others and teaching others how to act abound.

His legacy can be summed up by how he said he saw himself, “a very normal guy,” and how he hoped others saw him. “I just want to be remembered as a good man, an honest man, and one who lived up to his own beliefs,” he said.

Believe me, Mr. Scully, you will be.

Ready to dive deeper into the intersection of faith and policy? Head over to our Theology of Politics series page where we’ve published several long-form pieces that will help Christians navigate where their faith should direct them on political issues.

Notifications