Get a free copy of Parental Rights & Education when you subscribe to our newsletter!

In Part One of this series, we examined the pro-choice claim that the unborn is not a person, and we called this an argument from denial because it explicitly denies the personhood of the unborn. In response, we used the SLED test to show that there is good reason to believe that denying the personhood of the unborn requires one to make dubious distinctions between unborn and born persons.

In Part Two of this series, we examine the pro-choice argument from doubt, namely, that abortion is justified because we do not know whether the unborn are persons. We will call this an argument from doubt or skepticism. Unlike the argument from denial, the argument from doubt takes an epistemologically “softer” position by appealing to skepticism with respect to our ability to know the personhood of the unborn. That is, if we do not know, we should not say. In response to this argument, pro-life advocates may employ a counterargument from skepticism by using a technique called the “abortion quadrilemma.” By using the quadrilemma technique, pro-life advocates can show that skepticism should actually count against the morality of abortion, not for it.

The pro-choice argument from skepticism holds that we do not know whether or not the unborn is a person. It also asserts that since we do not know whether the unborn is a person, society should not restrict a woman’s right to abortion. The argument from skepticism has various forms, but its basic structure hinges on an inference from our lack of knowledge about the unborn to the conclusion that terminating the unborn is morally justified:

P1: If we do not know that the unborn is a person, then abortion is morally justified.

P2: We do not know that the unborn is a person.

C: Therefore, abortion is morally justifiable.

Does the conclusion follow from the premises? Does uncertainty with respect to the unborn morally justify abortion? It does not seem so. In fact, just the opposite seems to be true. Skepticism about the personhood of the unborn seems to count against abortion, not for it. In order to see this, we turn to a powerful (but seldom used) technique called the abortion quadrilemma.

First devised by renowned Christian ethicist Peter Kreeft, the abortion quadrilemma posits four ethical alternatives with respect to abortion and the uncertainty of the personhood of the unborn. It is a way of using formal principles of logic to show that abortion is not morally justified.

Before diving directly into Kreeft’s abortion argument, we should consider a hypothetical scenario having nothing to do with abortion as this will assist us in illustrating, objectively, why skepticism does not morally justify abortion.

Suppose two people are driving down a dark country road one evening on their way to a friend’s house. They suddenly come upon a large human-shaped object lying motionless in the middle of the road. They cannot drive around the object because it blocks most of the road. They see no signs of life. They see no one else around. There is no cell service. They are left with three options:

The driver honks, but no movement. The car creeps forward and still no movement from the human-shaped object. The situation seems uncertain, perhaps even dangerous. Is this a person? Are they hurt? Are they dead? Or worse, is it a trap? As they ponder these questions, the driver makes an executive decision to accelerate and run over the object. After a couple of bumps, the car clears the object and they are safely on their way again. The passenger looks at the driver in shock and asks, “What are you doing? You might have just killed someone!” To which the driver coolly responds, “Well, I didn’t know if it was a person, so don’t worry about it.”

What is wrong with the driver’s action? The answer is simple: The driver may have just run over a human being, one that may have needed their help. The driver did not know whether or not the object in the road was a person, but would his lack of knowledge justify his action? Probably not. In order for his actions to be justified, he would have needed to verify that the object either was not a person or was a mortal threat to his own life. If he could not rule out either of these cases, then his actions would be morally irresponsible.

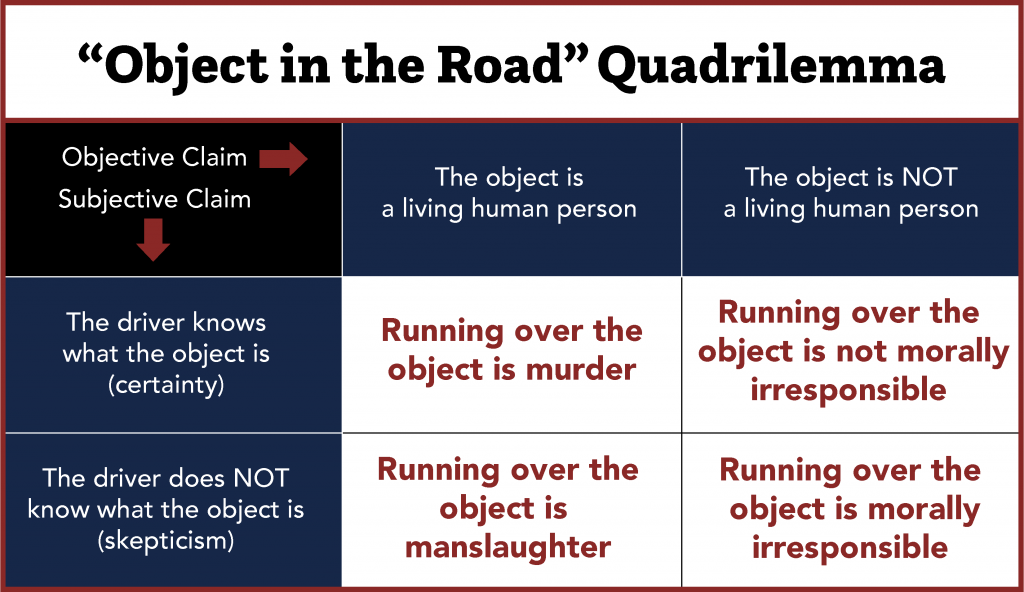

To demonstrate why the driver acted irresponsibly, we can simply use the quadrilemma technique.

Consider the two objective alternatives of the situation: The object in the road either is or is not a person. Next, consider the subjective alternatives: The driver either knows or does not know that the object in the road is a person. There are no other alternatives. Thus, if we combine the objective and subjective alternatives, we derive four ethical conclusions:

Most people acknowledge that human beings have a moral duty not to endanger other persons and to be reasonably certain that one’s actions are not endangering other persons. Hence, most people can easily ascertain why the driver’s action is morally irresponsible: He did not have reasonable certainty that the object in the road was not a person.

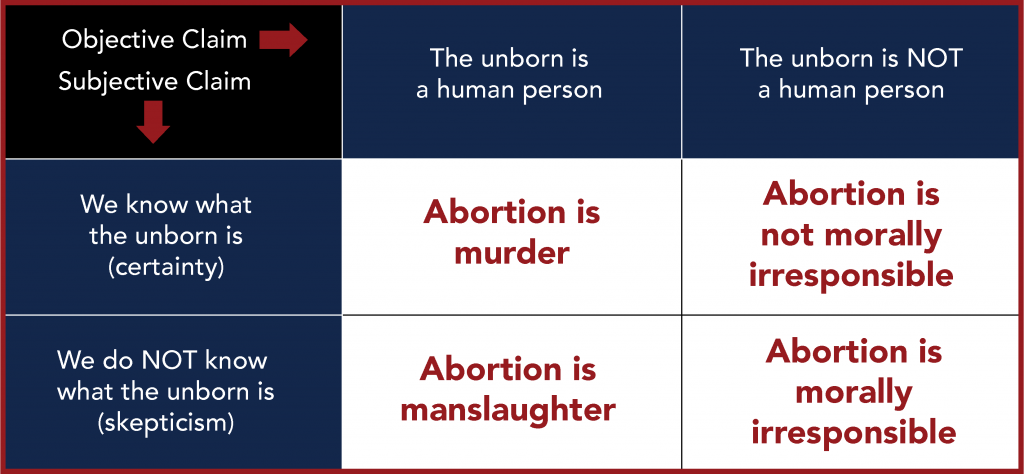

Turning to the issue of abortion, we can ask whether uncertainty with respect to the personhood of the unborn is enough to justify abortion. Recall that the pro-choice argument from skepticism requires one to assume that unless we know that the unborn is a person, then abortion is morally justified. However, if we apply this assumption to the scenario of the driver, we see why this assumption is untenable. Should we have to know that the object in the road is a person before we can question the driver’s actions? Of course not. If uncertainty does not prevent us from questioning the driver’s actions, then should it prevent us from questioning the morality of abortion? The answer is: No, it should not. In order to see this, we should turn to Peter Kreeft’s abortion quadrilemma argument. Notice that only the fourth option justifies abortion; the others do not:

Using Kreeft’s abortion quadrilemma, we can now flip the pro-choice argument on its head and provide a pro-life argument from skepticism:

Pro-choice advocates who attempt to justify abortion from skepticism about the personhood of the unborn should consider whether skepticism provides a moral justification in similar situations (such as the scenario of the driver and the object in the road). If uncertainty or skepticism is not a justifiable excuse in one situation, why would it be a justifiable excuse in another? If we have a moral duty to ensure we are not endangering persons on the road (or anywhere else for that matter), would we not also have a moral duty to ensure we are not endangering persons in the womb? Even though pro-life advocates can provide good reasons for believing the unborn are persons, they can still argue against abortion by using the abortion quadrilemma. The upshot of this argument is readily apparent: Skepticism cannot be used in defense of abortion — however, it can be used in defense of the unborn.

If you like this article and other content that helps you apply a biblical worldview to today’s politics and culture, consider making a donation here.

Notifications